- MAIN INDEX: Adolf Hitler Death and Survival: Legend, Myth and Reality

- The Bunker

- Hitler's Death?

- British Intelligence, Soviet Accusations and Rumours of Survival

- Soviet Investigations of Hitler's Fate

- Fabricating the Death of Adolf Hitler

- Hitler's Death or Survival

- Hitler’s Spanish Sojourn

- Hitler Sought Sanctuary in Japan?

- Bizarre Hitler Stories

- Hitler - Alive or Dead?

- Hitler Survives the Battle of Berlin

- New Investigations Question Hitler’s Suicide

- What If Hiler Had Survived

- Did Adolf Hitler escape from Berlin in 1945?

- Doubts on Hitler's Death

- How Hitler Survived

- Conflicting Stories of Hitler's Final Fate

- Unusual Stories of Final Days in the Bunker

- Hitler's Skull

- The Persistent Myth of Hitler's survival

- Did Hitler Die?

- The Death of Hitler

- Reopening the Hitler Conspiracy

- Hitler's Survival?

- Paraguay

- Did Hitler Escape to South America?

- Wilhelm Mohnke

- Hanna Reitsch

- Interrogation of Hanna Reitsch

- Martin Bormann

- "Downfall" [Der Untergang]

- Hitler in Books, Pulps and Advertising

There are few stories as enigmatic as the last days in the Berlin Bunker. Historians cannot agree on what exactly occurred 8.5 metres below the Reich Chancellery garden, providing for some intriguing theories.

There are few stories as enigmatic as the last days in the Berlin Bunker. Historians cannot agree on what exactly occurred 8.5 metres below the Reich Chancellery garden, providing for some intriguing theories.

Some bizarre myths have been spawned about the Bunker - people claimed the structure it had a dozen levels and that an underground railway line may have enabled Hitler to escape at the last minute.

There were myths, embellished by Hollywood movies, depicting the Bunker as being a lavish subterranean palace complete with a banquet hall and cinema.

Rochus Misch, a German Wehrmacht sergeant who was the SS telephonist in the Bunker, is one of the last surviving members of the entourage that was ensconced with Hitler in the Bunker in early 1945.

Now 88, he knows the mundane truth about the place and is eager to dispel the myths in frequent interviews.

"Too many myths were allowed to grow up about it - that it was a multi-story shelter, that it was capable of holding hundreds of people," he says.

"In fact, it was small and cramped and dingy and smelled of blocked toilets and Diesel fumes from the generator".

-- "The Sydney Morning Herald" 19 July 2006

Following the failure of the last German offensive in the West, a dispirited Hitler returned to Berlin on 16 January 1945 aboard his private train, the Führersonderzug.

While the train gathered speed toward Berlin, Otto Günsche. remarked within his hearing: "Berlin will be most practical as our headquarters: we’ll soon be able to take the streetcar from the eastern to the western front!" Hitler laughed wanly at this witticism, and the rest of his staff joined in.

As the long train wound its way through the devastated capital Hitler reportedly looked out at the ruins from his Pullman carriage, both surprised and depressed by the grim sights that greeted him. He needed no more than to look out the window to see the reality of his military failure, however, snowdrifts concealed Berlin’s cruelest injuries.

Arriving at Grünewald Station at 9.40 am, Hitler climbed down from the Führersonderzug for the last time and was driven in a convoy of armoured Mercedes to the Reich Chancellery, passing through bomb-damaged streets whose gutted and roofless apartment buildings and shops bore silent witness to the final collapse of the Third Reich.

The old wing of the Reich Chancellery, scene of his prewar political triumphs, had suffered unmistakably, and he could make out snow-filled craters in the gardens. A rectangular concrete slab elevated some feet above ground level marked the site of the deep shelter which Albert Speer had built for him. It looked an inhospitable place. Hitler decided to sleep in his usual first-floor bedroom for the time being—a hurricane seemed to have blasted through it, but it had been repaired—and to continue holding his war conferences in the ornate study overlooking the ravaged Chancellery gardens.

Martin Bormann—who returned from a two-week leave on 19 January, brought Eva Braun to Berlin with him.

By the end of the month the Soviets were only seventy miles from Berlin. Hitler continued to live in his apartments in the Old Reich Chancellery until mid-February before moving into the Führerbunker to sleep.

Built in 1738/39 by CF Richter, this building was originally constructed as an aristocratic palace. After several changes in ownership it was eventually bought by Otto von Bismarck, in 1869, for the use of the Prussian state government.

At the time Bismarck had his residence in the adjacent Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Shortly before, the Palais Voss had been demolished, the property subdivided and a section cleared for the construction of a new road – Voss Street. Bismarck wanted to prevent the same fate befalling the old Palais, and so the land was acquired for the German Reich in 1875. It was decided that the building would be used as a residence and headquarters for the Reich's Chancellor. The Palais was renovated in 1875-1878 by Georg Joachim Wilhelm Neumann. When the renovation was completed, Bismarck used the building as residence and headquarters. Since Bismarck directed the newly established Authority Central Bureau of the Reich's Chancellor, he proposed the renaming of the building to “Reich’s Chancellery” In the same year the building became part of international history when the Berlin Congress met here to regulate the problems in the Balkans.

The meeting took place in the reception hall, in the centre of the first floor, with Bismarck as mediator. In 1934-1935, the Palais was renovated once more, when Paul Ludwig Troost refurbished the building to serve as residence and office for Adolf Hitler. In 1938 Albert Speer rebuilt the entrance, and when he was commissioned by Hitler to construct the New Reich's Chancellery, he incorporated the baroque Palais into the architectural design of the new structure. From this time the Palais was called the Old Reich's Chancellery.

In March 1945, during the repair of bomb damage, the reception hall of the Old Reich's Chancellery was destroyed by a bomb. The entire building was destroyed between 23 April and 2 May 1945 by the intense artillery fire focused on the Reich's Chancellery during the Battle of Berlin.

Although Hitler continued to come up from the Führerbunker into both Chancelleries, to continue working in his study and used some of the building’s other rooms, he did not see the vast amount of damage that had been caused to both buildings by British and American aerial bombing. Staff officers visiting the Reich Chancellery for meetings had to take long and circuitous routes to reach Hitler’s Study, as corridors had been reduced to rubble by direct hits.

Although now safe from aerial attack, the Führerbunker was completely inadequate for use as a military headquarters as it was too small to accommodate sufficient staff or visiting generals attending conferences. It came to be described by many who visited it during the last weeks of the war as a fetid hole in the ground or a "concrete coffin". The Führerbunker had its genesis in air raid shelters built under and adjoined to buildings on Wilhelmstrasse and Vossstrasse in 1935.When the New Reich Chancellery complex was completed in January 1939 it included more air raid shelters.

Soon the Reich Chancellery would start to come under artillery and rocket fire from the advancing Red Army.

Adolf Hitler had planned already since 1934 an enlargement of the Reich's Chancellery Originally it was planned to only use Voßstraße 2-5, the properties already owned by the German Reich by this time. However By 1936, with the increasingly aggressive foreign policies that Hitler implemented, he also wanted

to demonstrate his power with a new big building.

So in early 1936 he gave Albert Speer the contract to build him a New Reichchancellery which should start at the Palais Borsig and stretch thenover the whole length of northern Voßstraße.

The construction began in 1937 and was completed in 1939.

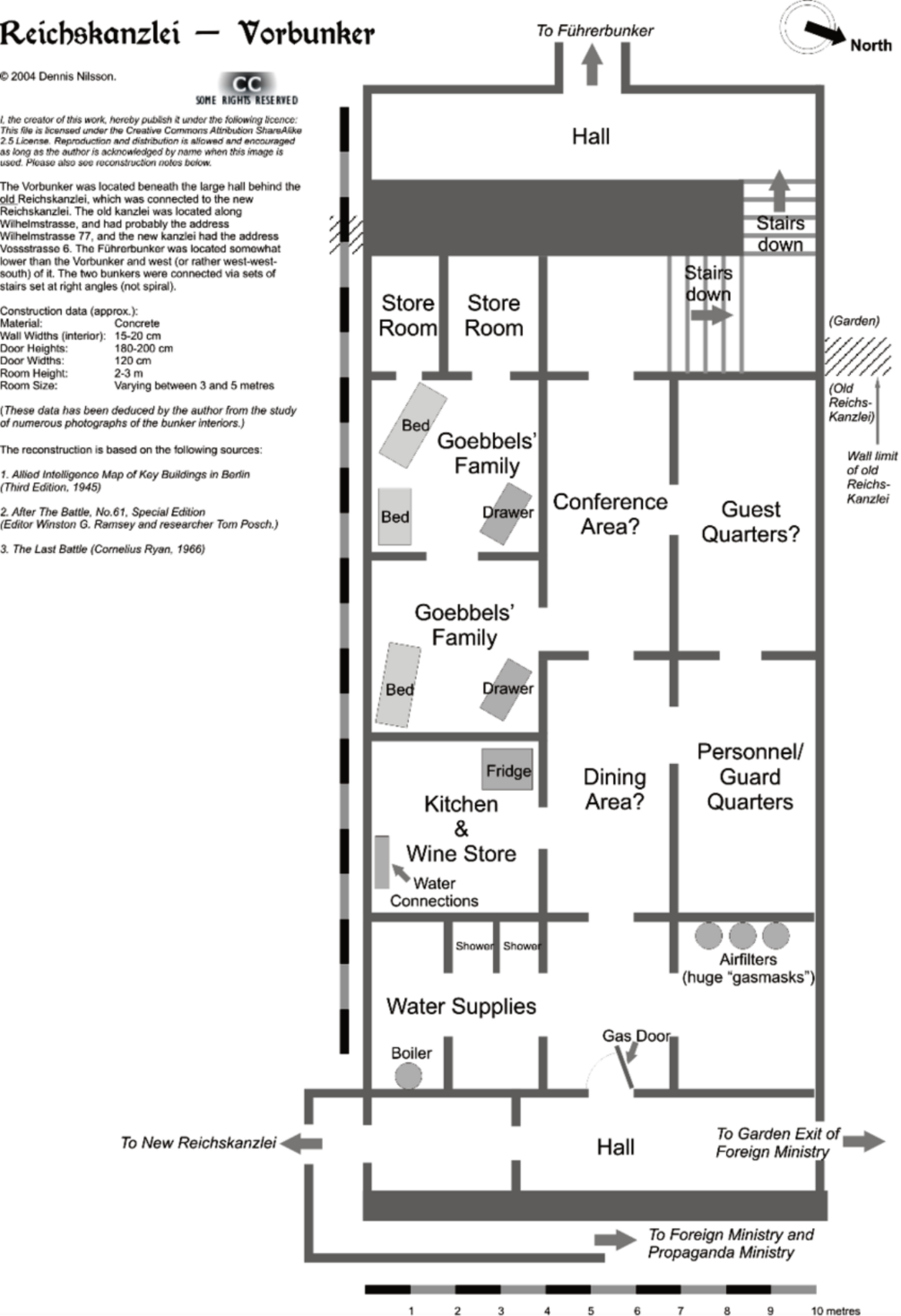

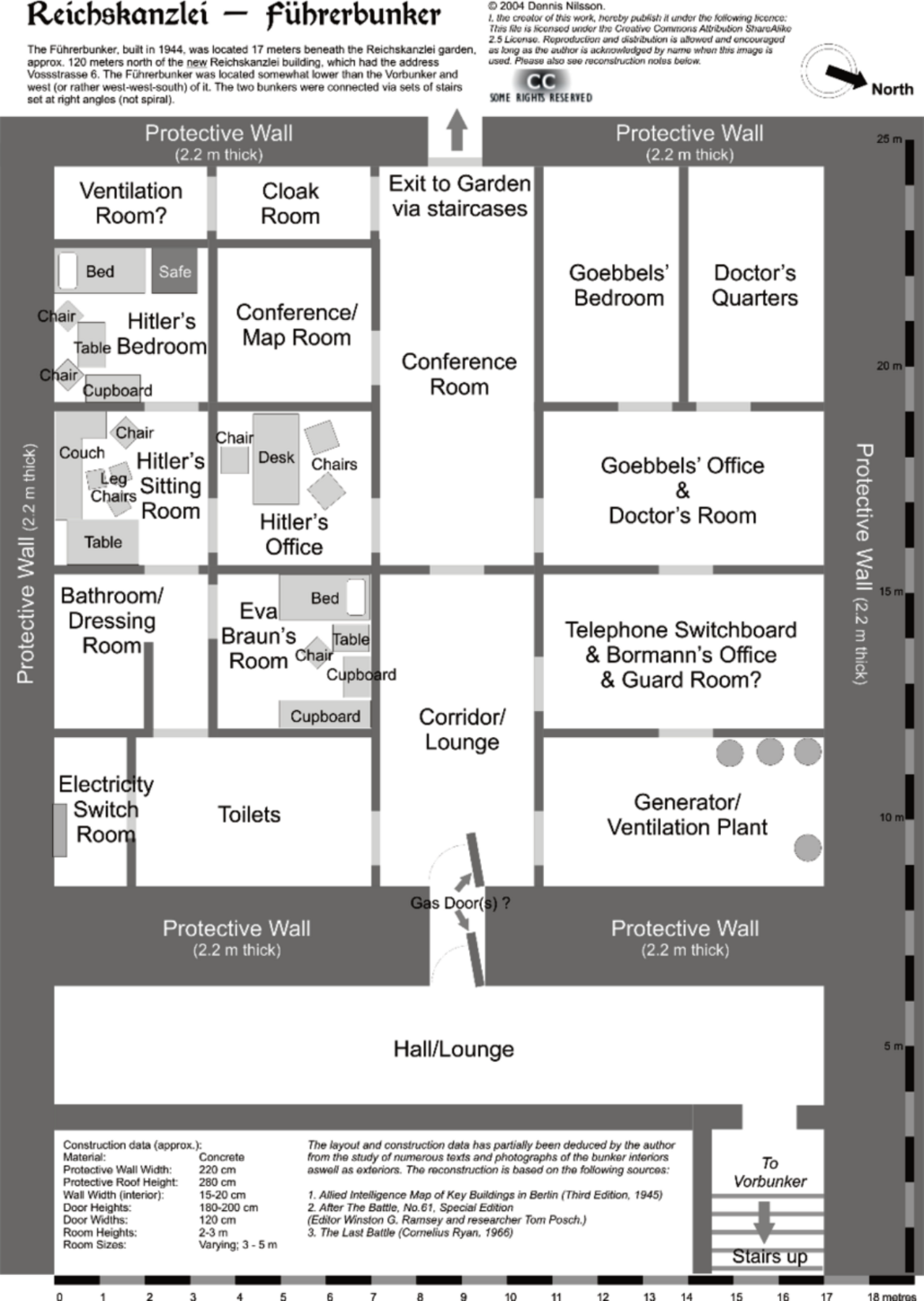

Entry into the Führerbunker was via the Vorbunker, passing down the dog-leg staircase, leading to a guarded door giving access to a long Hall/Lounge, where RSD and SS-Begleit-Kommando sentries checked identity papers before permitting entry to the Führerbunker proper.

Because of the constant bombing raids and air raid alerts Hitler decided to move his headquarters underground into the Führerbunker beneath the Old Reich Chancellery gardens in mid-March 1945.

Although now safe from aerial attack, the Führerbunker was completely inadequate for use as a military headquarters as it was too small to accommodate sufficient staff or visiting generals attending conferences. It came to be described by many who visited it during the last weeks of the war as a fetid hole in the ground or a ‘concrete coffin’. The Führerbunker had its genesis in air raid shelters built under and adjoined to buildings on Wilhelmstrasse and Vossstrasse in 1935.

When the New Reich Chancellery complex was completed in January 1939 it included more air raid shelters.

One was the Vorbunker, or Upper Bunker. Architect Leonhard Gall submitted plans in 1935 for a large reception hall cum ballroom to be added to the Old Reich Chancellery. Completed in 1936, the Vorbunker had a roof that was 5.24 feet [1.6 m] thick, the Bunker’s thick walls partially supporting the weight of the large reception hall overhead.

The air raid shelter and the reception hall were designed to form a static symbiosis. The shelter, with its thick concrete ceiling, formed a solid foundation for the marble columns in the reception hall.

These columns reached 50 cm downward through the air cushion beneath the reception hall floor, resting directly on the Bunker ceiling.

The placement of the pillars was also determined by the layout of the shelter. Each pillar was placed squarely on top of an intersection between two Bunker walls.

The extra pressure bearing down on these intersections added strength and stability to the air raid shelter.

This corridor was divided into two long rooms.

The first of these on entering the Führerbunker was the Corridor/Lounge.

A door on the left led to the Toilets and Electricity Switch Room. From the Toilets a connecting door led to the Bathroom/Dressing Room with Eva Braun’s bedroom/sitting room [also known as Hitler's private guest room], an ante-chamber [also known as Hitler's sitting room], which led into Hitler's study/office, on the right of the Bathroom.

There were two entrances into the Vorbunker; one from the Foreign Ministry garden and the other from the New Reich Chancellery. Both led to a reinforced steel gas proof door leading to a set of small rooms.

On the left was the Water Supplies/Boiler Room, to the right the Air filters Room.

The engine room was the technical heart of the Vorbunker. The generator was able to provide power for the Bunker even during a power failure. Left in the picture shown are the 4 air filters of the Bunker filter system. Only after filtering the air through these filters, was it then possible to distribute the air through the ventilation openings into the rooms of the Bunker.

Moving forward there was a middle Dining Area with a Kitchen to the left, which was where Hitler’s cook/dietician Frau Constanze Manziarly prepared the Führer’s meals. There was also a well-stocked Wine Store. To the right of the Dining Area was the Personnel/Guard Quarters. Moving forward again, there was a Conference Room in the middle and on the left two rooms that originally housed Hitler’s physician Dr. Theodor Morell and, following his dismissal in April 1945, Dr. Göbbels’ wife Magda and her six young children.

To the right of the Conference Room was a room used for guest quarters, two storerooms and then a stairway set at right angles connecting to the Führerbunker that was 8.2 feet [2.5 m] lower than the Vorbunker and west-southwest of it. Steel doors could close off the Vorbunker and Führerbunker from one another and the SS closely guarded all entrances and exits.

Hitler’s Führerbunker, or Lower Bunker, was built in 1942-43 28 feet [8.5 m] beneath the Old Reich Chancellery Garden 131 yards [120 m] north of the New Chancellery at a cost of 1.4 million Reichsmarks. It was deep enough to withstand the largest bombs that were being dropped by the British and Americans over the city.Designed by the architectural firm Hochtief under Albert Speer’s supervision, the Führerbunker was one of about twenty Bunkers and air raid shelters used by Hitler’s inner circle, bodyguards and military commanders in the region of the Reich Chancellery.

Albert Speer built two barracks for the "SS-Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler"

on the western edge of the Reich's Chancellery property.

These barracks were a part of the informal section of the Chancellery, and were not a part of the official government headquarters. Even though these buildings were planned and constructed in conjunction with the New Reichs Chancellery, Speer ensured that their design set them apart from the Chancellery itself. He achieved this by utilising a more functional architectural style typical of residential buildings. Here the difference between the ornate architecture of official government buildings and that

of purely utilitarian structures can be clearly seen.

Many cellars in the surrounding buildings were also utilized as auxiliary Bunkers during the Battle of Berlin.

Mittelbau [literally "Centre Building] was the physical and political centre of the New Reich's Chancellery. The Reich's Cabinet Room, the Grand Reception Hall, the Marble Gallery and Hitler's office were all located within this section of the Chancellery. This central role of Mittelbau was outwardly indicated by its prominent placement, size, and the materials used in its facade. The street facade was covered with a natural stone cladding, and showed no visible access to the building. This gave the building section a somewhat fortified appearance, which was further emphasized by a recessed facade, 16 meters from the road. However, this exclusive appearance was simply an illusion of design - in actuality Mittelbau was constructed on top of a public air raid shelter. Five hidden entrances to the shelters were located in the paving in front of the building. These entrances could be opened independently from within the Chancellery. They opened hydraulically to provide access to stairways leading to the air raid shelters.

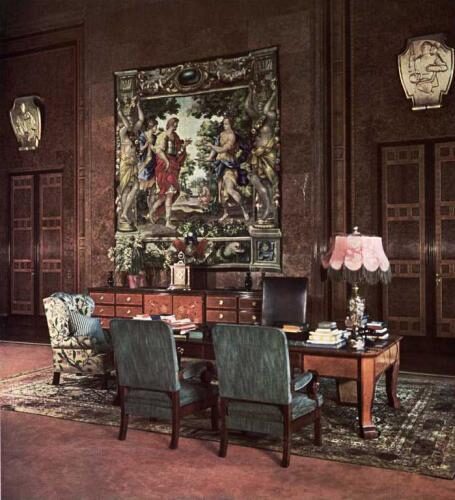

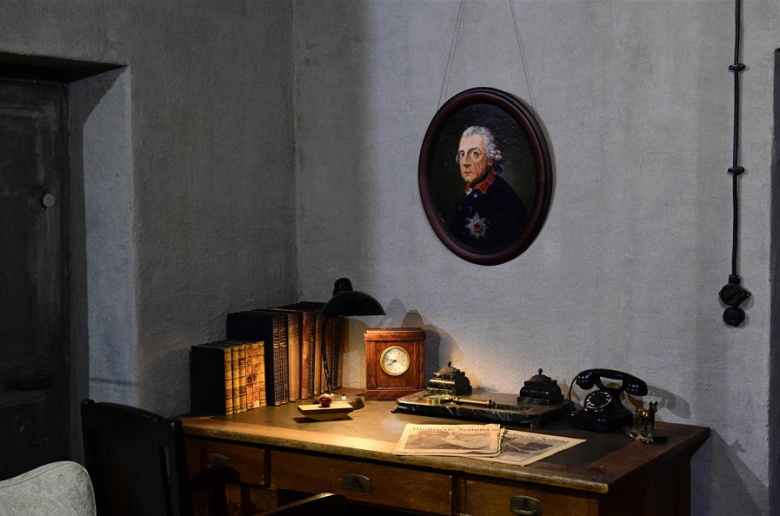

Hitler's private rooms were a bedroom with army bed, wardrobe, chest of drawers, and a safe; and a tiny, low-ceilinged living room with desk, table, and hard upholstered sofa. A large portrait of Frederick the Great, that Hitler would spend much time staring at as the Soviets fought their way into Berlin’s suburbs, hoping that he could emulate Frederick and turn back the Bolshevik horde with some final grand military gesture, hung over the desk.

Hitler's accommodations by February 1945 had been decorated with high-quality furniture taken from the Chancellery, along with several framed oil paintings.

A door connected Hitler’s Sitting Room with Hitler’s Bedroom. A door on the right of Hitler’s Study led back into the central corridor, this section is called the Conference Room.

The last three rooms on the left of the Führerbunker were not connected to Hitler’s suite and consisted of the Map conference/map room [also known as the briefing/situation room] which had a door that led out into the waiting room/ante-room.

Hitler held most of his military situation conferences during the last weeks of the war, in the Cloakroom and a Ventilation Room.

The garden facade of the New Reich's Chancellery reached over the entire length of Mittelbau, and one quarter of the two administrative buildings. The focal point of the garden facade was the terrace with portico which led to Hitler's office. The terrace was flanked by two bronze horses, created by the Austrian sculptor Josef Thorak. Two staircases to the left and right of the terrace led to the portico with it's giant marble

pillars from which doors led to Hitler's office.

The Führerbunker suffered from noise caused by the steady running of aeration ventilators twenty-four hours a day and also had a problem with cool moisture on the walls as Berlin has a very high ground water level.

The exit of the Vorbunker was located opposite the elevator. It is likely that this exit was used as a second entrance to the Vorbunker. While the residents of the Old Reich Chancellery used the main entrance to the Vorbunker, at the same time the residents of northern extension could enter the Vorbunker through the air lock of this Bunker exit.

The left side of the Führerbunker consisted, moving from the staircase connecting it with the Vorbunker to the emergency exit to the Reich Chancellery Gardens, of a series of rooms. First was the Generator/Ventilation Plant Room. This was connected to the Telephone Switchboard Room where SS-Oberscharführer Rochus Misch of the SS-Begleit-Kommando worked, Martin Bormann’s Office and the Guard Room. Hitler’s loyal Valet SS-Obersturmbannführer Heinz Linge lived here. Next were two rooms: Göbbels’ Office and the Doctor’s Room.

The last two rooms on the right of the central Conference Room were Göbbels’ Bedroom and the Doctor’s Quarters. Parts of the two Bunkers were carpeted and one section of this material was recently discovered in a British regimental archive. It reveals that the carpet had a floral pattern of yellow flowers and blue leaves on a fawn background. The rooms were furnished with expensive pieces taken from the Reich Chancellery above and there were several framed oil paintings on the walls. But the interior, in keeping with Hitler’s other field headquarters, could not be described as anything other than Spartan and functional.

Replica of Hitler’s Study in the Bunker

It was built about a mile from the

original site by a private company

"Historiale" which also runs the

Berlin Story Museum next door.

Credit: Gordon Welters

"The New York Times"

The Nazis' Last Stand

World War II's ferocious and surreal conclusion on the Eastern Front

Norman Stone

The Atlantic

June 2002 Issue

We in the Western world equate the end of World War II with the Ardennes offensive—the Battle of the Bulge. Just before Christmas, 1944, in a thick fog that protected his tanks from Allied aircraft, Hitler gambled by launching a sudden counterattack in eastern Belgium, in difficult country, and brought off a tactical coup. His troops overwhelmed the surprised defenders, and it looked as if he would cut them off and reach the Allies' big supply port at Antwerp. But an American general famously said "Nuts" when called upon to surrender, and the fog lifted. The last German offensive in the West speedily crumbled, and from then on, though there was tough fighting in some places, the British and the Americans were able in many others just to walk forward, accepting the surrender of hundreds of thousands of Germans who were grateful to be giving up to the Western powers and not to the Soviets. Anglo-American captivity was not comfortable, particularly in the first few weeks, but at least the prisoners [in the main] could survive. Soviet captivity was a different matter. Of the 90,000 men who surrendered at Stalingrad in January of 1943, only 6,000 made it back to Germany, more than ten years later. The Soviets were not in a forgiving mood. The Fall of Berlin 1945 makes this very—perhaps excessively—plain.

The final Western land campaign against Nazi Germany may have been something of an anti-climax. But on the Eastern Front the war came to an end apocalyptically, and Antony Beevor, a veteran military historian, has a first-rate subject for his talents. To Central Europeans with a historical sense, it must have seemed as cataclysmic as the Mongol invasions, seven centuries before. Millions of Red Army soldiers, thousands of tanks and aircraft, had lined up on the River Vistula, which bisects Poland from north to south. On 12 January 1945, they struck, with great howls of artillery and multiple-rocket launchers—"Stalin Organs," the Germans called them. Already, the preceding summer, a whole German army group had been ground down by this massive weight, and the local commanders were desperate to be allowed to retreat, to show some flexibility in defense. Hitler, by now madly obstinate, told them that they must hold on; he even had generals shot for treachery and defeatism if they disobeyed. The outcome was foreseeable: the German defense disintegrated. One after another, supposed strong points became engulfed in the Soviet flood, and one after another, Polish cities were liberated—Warsaw, a heap of ruins because the Germans had burned it in revenge for the Polish uprising of August 1944; Kraków, a Renaissance jewel of a town, which survived intact because the Soviets were too quick for any defense to operate. On 27 January came a melancholy capture: Auschwitz. Most of its surviving prisoners had been evacuated by the Nazis in a death march a week or two before, and were now moving, a column of pajama-clad scarecrows, toward concentration camps in Germany. By the time the Red Army had outrun its supply lines and needed to refit its tanks, it stood at the River Oder, at most fifty miles from Berlin.

An argument ensued. Should the army push straight on to Berlin, as its outstanding commander, Marshal G. K. Zhukov, wanted? With this there were problems, which Beevor outlines well. In the first place, Soviet generals were even more given to personal rivalry than Western generals, and some of them were not at all keen for Zhukov—by far, and justly, the best known and best respected of them—to achieve the renown for taking Berlin. Additionally, as ever in wartime, there were powerful arguments for prudence. Even as the German army was clearly on the run, the Soviets feared it. German soldiers remained formidable to the end, and as the Ardennes offensive had shown, they were quite capable of pulling surprises. The Soviets had advanced a long way from the Vistula, but fortified pockets of German troops remained—around Königsberg, the old Prussian capital, and Danzig, at the mouth of the Vistula; at Breslau, in Silesia, and the Hungarian capital, Budapest, where they were desperately withstanding a siege that was to last six weeks and to tie down R. Y. Malinovsky's army group. In Courland, in Latvia, a considerable contingent was still impregnably fortified, and supplied by sea. Suppose that these forces all counterattacked simultaneously, with the "wonder weapons" that the Nazis were supposed to be producing: would this not spell a Soviet disaster? After all, in the early summer of 1942 Stalin had assumed that after his victory at Moscow, when the initial German onslaught had been stopped, the way was open for a grand counterattack. Instead he had run into a trap, and had faced a triple defeat—in Kharkov, in the Crimea, and in Leningrad—that allowed the Germans to attack again, this time across the great plains of southern Russia. Much better, if Stalin did not want to risk a similar humiliation, to concentrate on reducing the pockets one by one. And so into early April the Red Army was kept busy with a kind of grinding, inch-by-inch frontal attack on fortified lines—an attack that no Western general, mindful of the need to keep casualties down, could possibly have ordered.

For the Germans this was by far the worst period of the war. They knew that when the Soviets arrived, there would very likely be an orgy of rape—old women, young girls, whoever. Beevor goes on and on about this. He has interviewed women who remember these horrors. The book has been rather badly received in some Russian quarters, because—at least in the captured cities, where officers could keep order—Red Army soldiers [as opposed to those in their wake, camp followers and former prisoners] were under some sort of control; and in any case, the previous German occupation of a large part of Russia and Ukraine had been distinguished by extraordinary cruelty and pillage. But there is no doubt that rape on a grand scale distinguished the Soviet advance through the countryside; and even before the end of the war Churchill was asking himself how he and the Americans could have let such "barbarians" into Europe. To the Soviets, however, the Germans had been the real barbarians, and Stalin was not going to let them forget it. Not until some days after the end of the war did it all stop—and then only because the Soviets needed at least some German cooperation.

The Nazis had forbidden anyone to retreat from eastern Germany. To stanch the Soviet invasion they even [grotesquely, as Beevor captures well] organized young boys and old men into a Volkssturm [typically pompous, untranslatable Nazi language; "enraged territorials" is probably close enough].. Then, at the last moment, civilians were allowed to flee. In the millions they did—column after column of horses and carts, laden with family valuables, sick old people, children, and pregnant women, plus a few able-bodied men who were trying to keep order. There was panic and death as the civilians were evacuated across the sandy spits of the Frisches Haff and in the Wilhelm Gustloff, which a Soviet sub sank in the freezing Baltic, with the loss of 7,000 lives.

Beevor may have missed an authorial trick or two here, because these treks, as they were called, profoundly marked the consciousness of the German people. He might have referred to Alexander Dohna-Schlobitten's classic "Erinnerungen eines alten Ostpreussen" [Memoirs of an Old East Prussian]. A trek is difficult to describe, in that the same things happen again and again: wheels are lost; snowdrifts prove impassable; a road is unexpectedly blocked by Soviet cavalry; a baby is born prematurely after the mother's nighttime trudge through a blizzard toward the only light for miles around. Dohna-Schlobitten—a prince, with extremely interesting observations on the relations among the old aristocracy, the army, and the Nazis—managed to describe one trek, from deepest eastern Prussia to safety beyond the Elbe, in such a way as to keep the reader absorbed over about a hundred pages. The book was, unsurprisingly, a best seller in Germany, in part because so many Germans had been affected by such events.

When trekkers arrived in the vicinity of Berlin, they would see at night, on the horizon, a huge dull-red light, punctuated by blinding flashes: the Anglo-American bombing of their capital, which in the end reduced much of the place to a lunar landscape. The railway stations of Berlin were crammed with refugees, who spilled over into the underground railway tunnels. Unfortunately, Beevor is too much the military man to spend time on civilian life. That is a pity, because its fantastic incongruities might have varied the pace somewhat. Amid all the chaos the Hotel Adlon was still functioning, its waiters in white gloves and tails serving the diplomatic corps—the Irish minister, the Croat minister [a competent novelist], the Vichy French minister in exile, members of the poor Japanese mission. In the railway tunnels stalwarts of the foreign volunteer SS [including even a few British] strutted their stuff, expecting Soviets any minute to come around the next bend. The Frenchman Louis-Ferdinand Céline managed to evoke this kind of black surrealism with "Nord", and the Italian Curzio Malaparte conveyed a similar mixture of ribaldry, evil, and pettiness, with the same gusto, in "Kaputt". No German has ever brought off a similar literary feat.

When the Soviets had finally wiped out the pockets [it took them weeks], they assembled their forces on the Oder and readied them for a full-scale strike directly at Berlin. It was the middle of April, and by then Hitler's defenses had been largely neutralized. Since the autumn of 1944 it had been possible for the Americans, especially, to conduct daylight pinpoint bombing raids on fuel installations and transport lines. [The innovation of aluminum-and-wood fighters, light and fuel-efficient, and therefore able to protect heavy bombers on long-range missions, was unmatched elsewhere.]. And this advantage in the air was passed along to the ground troops, because the German defenders were almost immobilized for lack of fuel.

German-made jet fighters might have worked wonders in the air, but fuel was so short that they had to be towed to the airfields by oxen, and most were destroyed on the ground in Munich.

Hitler could rant and rave from his underground headquarters, could stage his daily situation conferences with all the airs of a Napoleon at Austerlitz; but the troops he ordered to do this or that were basically left without the means to move, and thus could not mount a coordinated defense. They could only wait for the Soviets.

And the Soviets arrived, beginning in mid-April. Many others have written on this subject. Cornelius Ryan ["The Last Battle"] was very good, and the late John Erickson ["The Road to Berlin"], who has done more for the study of the Soviet military than anyone else, was outstanding. Beevor's specialty here is disentangling the street fighting [as it was in his book "Stalingrad"]. Street fighting, like the treks, is in many ways just the same thing happening again and again. But here we have a sense of the Soviets moving in [the book could do with a proper map of central Berlin] as they fought over those parts of the city that the world would come to know so well in Cold War days—Zoo, Friedrichstrasse, Unter den Linden, Vosstrasse, Siegesallee. The Germans fought to the death rather than surrender. [[Beevor offers a very British-army aside when he says that British officers regarded the war as a good fight against a reasonably sporting enemy.]. In the midst of it all, in a two-story concrete structure deep beneath the garden of the severely neoclassical Reich Chancellery that Albert Speer had built for him, sat Adolf Hitler.

It is a pity that Beevor lacks a sense of the surreal, because Hitler's end almost gives the word new meaning. The Führer would have liked to perish heroically, by his own hand, in the middle of a twilight of the gods. Instead there was a persistent ridiculousness about his last weeks, and it worked up to a climax. The Russians have still not revealed the goods the Soviet archives must surely have on this; we know some of the story, but not all. Buoyed by some kind of insane determination, Hitler neglected every opportunity to surrender to whichever of the Allies might have received him most sympathetically. The situation conferences went on; the black-clad figures clicked their heels; on occasion Wagner or Bruckner was played. [When Hitler committed suicide, the Reich Chancellery staff, with huge relief, raided the wine cellar and put on jazz records; some staff members were dancing tipsily when the Soviets burst in].

Meanwhile, battalions gave way, and the Soviets advanced relentlessly until they were fighting on several stories of the old Prussian Finance Ministry, down the street. At that point Hitler staged his wedding, of all things, made polite conversation with the witnesses, and, the next day, gobbled down a vegetarian lunch and shot himself while the bride munched cyanide.

Desperate that his body not be defiled, Hitler had given orders for it to be burned. Seven faithful worthies trudged up the steps of the underground shelter, lugging the corpses of Mr. and Mrs. Hitler in Wehrmacht blankets. The bodies were laid in the garden and drenched with petrol that had been brought from the emergency reserve of the Chancellery garage; then matches were lit. But nearby shelling temporarily reduced the oxygen in the air, and the flames went out. One of the group produced the sort of paper spill with which one lights a pipe, and Martin Bormann, Hitler's deputy, applied a match. The spill flew through the air like a paper dart and found enough oxygen to ignite the corpses, and the party returned downstairs. [There they lit cigarettes, the smell of which, through the ventilator shafts, alerted others in the Bunker to the Führer's death, because he had been fanatically anti-smoking to the end].

But the would-be cremators had not realized that cremation requires a draft of air beneath the body. Hitler and Eva Braun burned superficially, and then the flames went out again. The bodies were identified for the Soviets by one of their captives, and autopsies were performed. Then the Soviets mysteriously denied that they had the bodies after all, and suggested that Hitler might have escaped somewhere. Why did they do this? We still do not know. In any event, the Soviets jumbled post-autopsy bits of Hitler's body among the bits and pieces of several other bodies, including possibly his dog's, and the Third Reich ended with, ironically enough, an inefficient cremation. It is a theme for Céline.

Hitler Kaputt: How Stalin Learned About the Führer's Suicide

Sputnik/Military & Intelligence

09.05.2018

On 1 May 1945, Marshal Georgy Zhukov sent Soviet High Command in Moscow perhaps the most important report in four years of war, informing Josef Stalin about Adolf Hitler's suicide.

At 4 am on 1 May 1, a group of Wehrmacht officers with white flags appeared before Commander Vasily Chuikov's 8th Guards Army, requesting a meeting with OKH Chief of Staff Hans Krebs, who claimed to have an extremely important message to deliver. Signed by Nazi Party chief Martin Bormann and Propaganda chief Josef Göbbels, the message, addressed directly to Stalin, read:

"Berlin. April 30, 1945. The Imperial Chancery. Message. We authorize Army Chief of Staff General Hans Krebs to deliver the following message: 'I inform the leader of the Soviet peoples, as the first of non-Germans, that today, on 30 April 1945, at 3:50 pm, the leader of the German people Adolf Hitler committed suicide".

The unusually cordial tone of the message, given the Nazis' previous efforts to murder and enslave the "Untermensch [subhuman] masses from the East", was not the result of any change of heart. Rather, the Nazi Bonzes were looking to end the war through peace negotiations. The document states that Göbbels and Bormann were looking "to clarify to what extent it is possible to establish the basis for peace between the German people and the Soviet Union, which will serve to the benefit of both peoples suffering the greatest losses in the war".

Chuikov's talks with Krebs lasted five hours, with the Soviet commander inquiring about the circumstances of Hitler's death. The response was that the Fuhrer had killed himself in Berlin, and that his corpse was burned in accordance with his will. Chuikov was also told that Göbbels, the new leader of the Third Reich, did not intend to announce Hitler's death to the German people for political reasons, fearing that Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler would use the news to form his own government.

Himmler had had a falling out with the Führer in the last month of the war amid rumors of secret negotiations between the Reichsführer and representatives of the Western Allies. On 29 April 29, 1945, a day before committing suicide, Hitler stripped Himmler of his membership in the Nazi Party.

Krebs' mission failed. Soviet command flatly refused to negotiate, saying it wouldn't accept anything less than unconditional surrender. The same day, Göbbels responded, refusing to agree to the capitulation of the Berlin garrison. At 10 pm Göbbels and his wife committed suicide, taking their six children with them. The same night, General Krebs too committed suicide in the Führerbunker. Bormann was killed attempting to break out of the Soviet encirclement. Berlin surrendered on 2 May. Himmler would live on until 23 May, taking a fatal dose of cyanide while being interrogated at a British POW camp, where he had attempted to disguise himself as one sergeant Heinrich Hizinger.

Stalin learned about Hitler's death immediately after Krebs arrived at the Soviet headquarters. Marshal Georgy Zhukov later confirmed that Stalin asked Krebs questions directly in messages passed on between himself and Chuikov.

Initially, Stalin reacted to the news of the death of his mortal enemy with skepticism. On 2 May 2, news of his demise was reported by German radio, which said that the Führer "died with a weapon in his hand defending Berlin"." The Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union immediately voiced its skepticism, suggesting that the report was a "stunt," and that "by disseminating this statement on Hitler's death, the Nazis are clearly hoping to give Hitler the opportunity to step down from his post and go underground".

Soviet archives made public after the USSR's collapse revealed that Hitler's remains were exhumed and reburied repeatedly, for the last time in April 1970, when the KGB exhumed boxes at a SMERSH facility in Magdeburg and destroyed them. The remains of a lower jaw with dental work found by the Red Army on 5 May 1945 confirmed that the remains really did belong to Hitler.

The nearly forgotten remains of the Nazis' Bunker complex were rediscovered In 1986

The East German government made plans to erect a large apartment complex on the corner of Vossstrasse and Otto Grotewohl Strasse, now known as Wilhelmstrasse.

In order for those Socialist blocks to go up, concrete from a darker past had to be demolished first. The ground under the construction site turned out to contain not only Adolf Hitler's former Bunker, but also the remains of an air raid shelter used by the Neue Reichskanzlei, or New Reich Chancellery, and the foreign ministry.

This required the excavation of massive reinforced concrete walls located up to eight meters {26 feet] deep in the ground, which had to be removed and demolished piece by piece, a laborious undertaking.

The victorious Red Army had given up on the "Führer's Bunker" back in 1947, after Soviet soldiers attempted to blow it up.

They were able to destroy the complex's ventilation shafts, collapse interior walls and even cause the four-meter-thick [13-foot-thick] Bunker roof to drop by 40 centimeters [15 inches] from the force of the explosion, but the rest held.

This was followed by further blasts 12 years later, but then the East German government filled in the entrances to the ruin of Hitler's Bunker, dumped dirt on top of the site and let grass grow over the whole thing in the truest sense of the phrase.